“Every person has the power of vision. There is no need to be visionaries. However, one must acknowledge that at last one can see for oneself. Every identity has its own imaginal world but if one accepts the prepackaged images they foist on one well, god help us! I hope that you, benevolent viewer, are able to give free rein to your untamed power of observation. It is the only way you will be able to see this different world of images. Here is a taste.” Stefano Arienti was born in Asola (Mantova) in 1961, but Milanese by adoption. His work is driven by the struggle to snatch the viewer from the onslaught of images – a veritable tyranny, according to the artist – that asphyxiates contemporary life. This results in constant experimentalism, consisting of an infinite range of materials and techniques. Of the more recent additions to this list, textile canvasses mark a further stage on his “paradoxical route to painting”. His desire to measure himself against one of the principal techniques used in textiles – tapestry- made him the ideal person to take on the project presented by Fondazione Malvina Menegaz per le Arti e le Culture of Castelbasso (Teramo in Abruzzo) on the occasion of the Italian Council competition. Retina is born of the idea to reveal the contemporary potential of a technique whose origins are as remote in time as they are geographically and culturally widespread.

“Every person has the power of vision. There is no need to be visionaries. However, one must acknowledge that at last one can see for oneself. Every identity has its own imaginal world but if one accepts the prepackaged images they foist on one well, god help us! I hope that you, benevolent viewer, are able to give free rein to your untamed power of observation. It is the only way you will be able to see this different world of images. Here is a taste.” Stefano Arienti was born in Asola (Mantova) in 1961, but Milanese by adoption. His work is driven by the struggle to snatch the viewer from the onslaught of images – a veritable tyranny, according to the artist – that asphyxiates contemporary life. This results in constant experimentalism, consisting of an infinite range of materials and techniques. Of the more recent additions to this list, textile canvasses mark a further stage on his “paradoxical route to painting”. His desire to measure himself against one of the principal techniques used in textiles – tapestry- made him the ideal person to take on the project presented by Fondazione Malvina Menegaz per le Arti e le Culture of Castelbasso (Teramo in Abruzzo) on the occasion of the Italian Council competition. Retina is born of the idea to reveal the contemporary potential of a technique whose origins are as remote in time as they are geographically and culturally widespread.

“Retina is part of this continual exchange, a project that allows Abruzzo to “export” to the rest of the world – in this specific case to Barcelona – a work of art that comes from Stefano Arienti’s rereading of the tapestry tradition of Penne. The work is symbolic of a new dialogue involving art and craftsmanship, each reinventing and revitalising the other. The triptych of tapestries was produced by the artist during his stay at the workshops in Penne, in the province of Pescara. It reveals to an international public the contemporary possibilities of an extremely ancient technique, combining art and Italian manufacturing excellence.” stated Angelo Gioè, director of the Italian Cultural Institute in Barcelona.

“Fondazione Menegaz, while systematically structuring its activity in the medieval town of Castelbasso, where it was founded and where its headquarters are, has run cultural projects year after year without fail, resulting in exhibitions aimed at opening Abruzzo up to the world. This has led to a manifold dialogue with expressions of contemporaneity, specifically in terms of art, in light of a desire to establish roots in a consciously glocal dimension” stated Osvaldo Menegaz, president of Fondazione Malvina Menegaz per le Arti e le Culture.

Interview with Stefano Arienti by Paolo Di Vincenzo

Maestro, your core work for the project of Fondazione Malvina Menegaz per le arti e le culture curated by Simone Ciglia, are three large tapestries, which are a continuation of your work on the condition and potential of the image. How did you come up with this work?

It is a work of photography. Up to now, I haven’t done much photography but I did some in the past and I tried to make it personal. In this case, I used a mix of traditional and innovative, digital techniques in order to transform the image into a special, textile object such as a tapestry.

You start from a photograph which, by being submitted to a halftone process, is turned into a tapestry. Can you describe the stages of the process in more detail?

I start with a digital image, though it might just as well be analogical, and, by using very simple computer programmes, I transform it from a colour to a black and white photo and then into two colours. The halftone process serves this purpose, to simplify the image while conserving as much detail as possible. There are many parameters I can modify or use to produce a more contrasting or legible image or where the halftone process destroys the possibilities of the photo a little further. I decide on the point, the result I want to achieve.

With Retina you engaged with a very solid Abruzzo tradition, Arazzeria Pennese, founded over 50 years ago. They have worked with some very important names, not least your own. This is the fulcrum of the project which was so successful in the international competition: combining extremely high-quality craftwork with art in order to promote Abruzzo in Italy and abroad. How have you found working with local craftspeople?

It has been a wonderful experience. I hope I have been able to learn a few things I didn’t know before. It is the first time I have produced a work involving a rather complicated textile-making process, which can be either manmade or computer generated, as it usually is nowadays. However, my aim is for the image to rest on an object which is made of very special, unique material. Therefore, I want to learn about the sensibility which developed the type of know-how surrounding these special objects and I hope to offer a sensibility that comes from the contemporary art world to those who are willing to work with me.

The revival of crafts and tradition lies at the heart of Fondazione Malvina Menegaz’s long-term project. In your opinion how does this initiative fit into this scheme?

It is certainly an experimental project. I hope it can engage with and revive traditional know-how, unlike contemporary technologies and the sensibility of contemporary photography. These are images we all produce using technological and digital devices that are increasingly complex yet increasingly available to everyone.

What lay behind the choice of the three subjects of the tapestries?

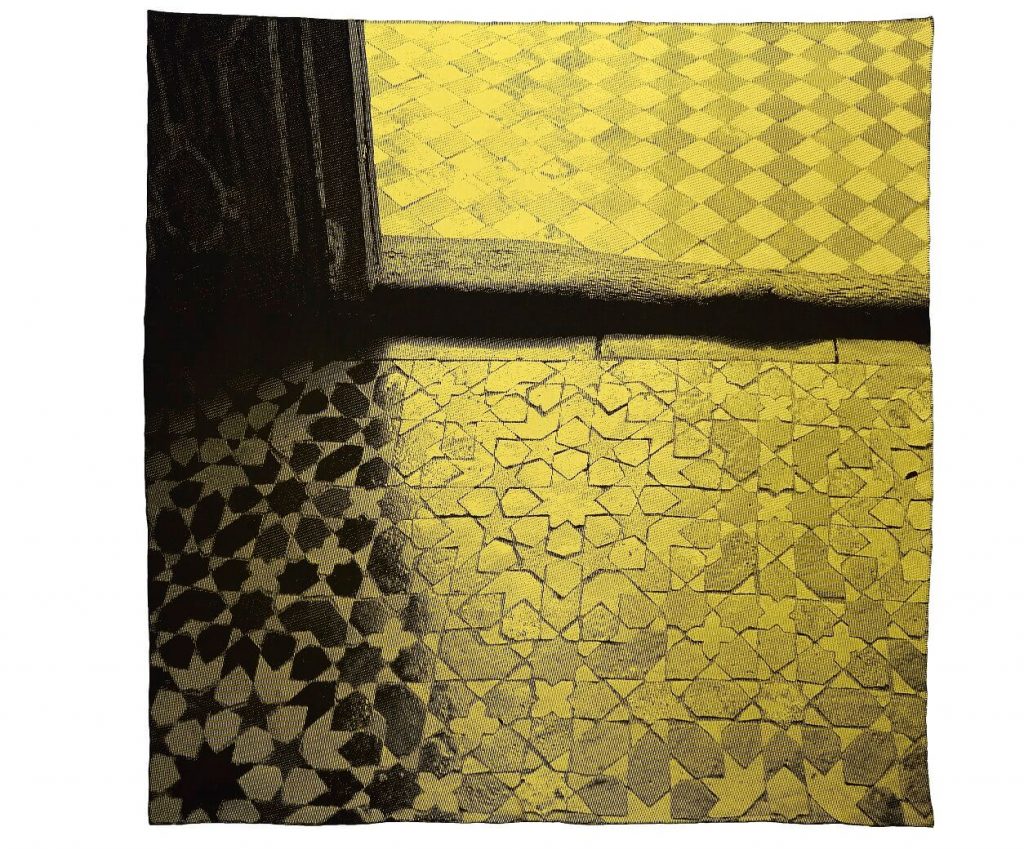

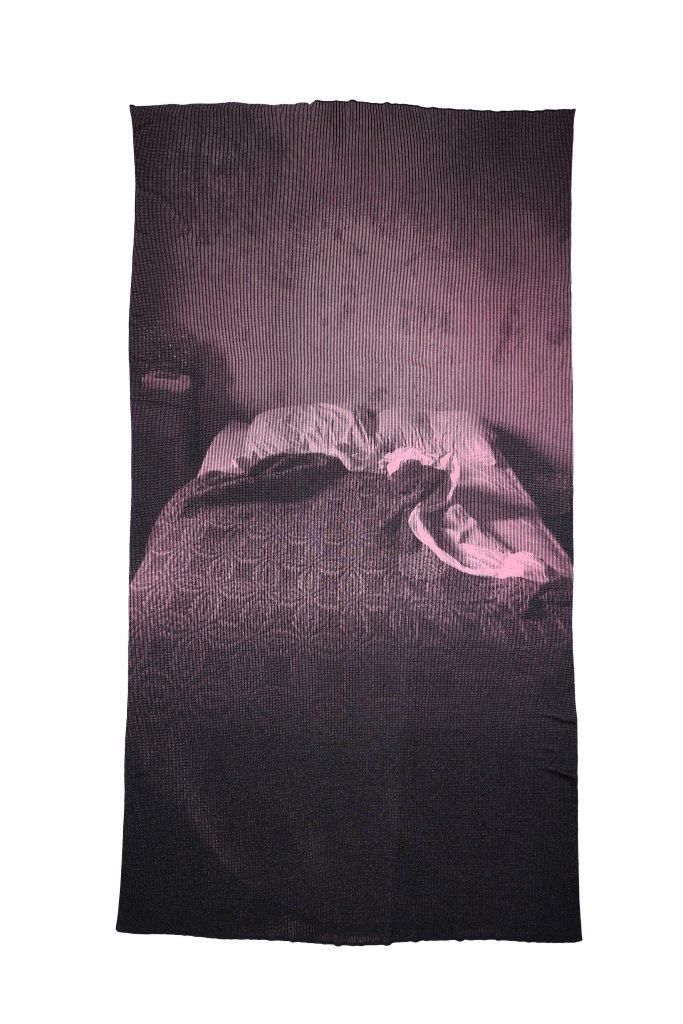

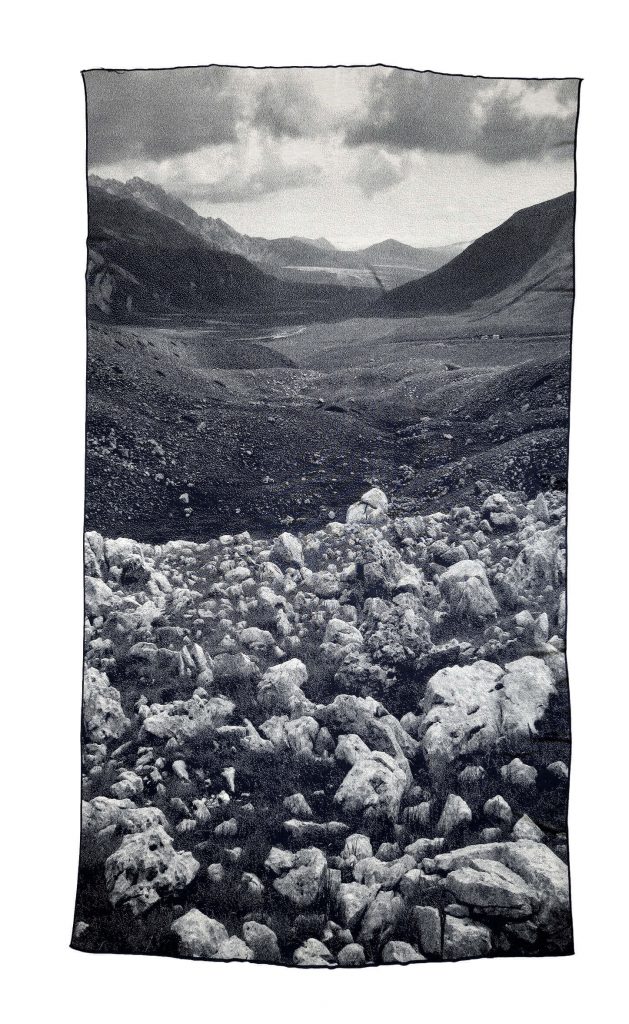

They are very different images from one another. One was taken at Museo Batha in Des, in Morocco, and shows a floor with light reflecting on tiles. It has contrasting colours of yellow and black. Another is an Abruzzo landscape, a detail of Campo Imperatore, a photo I took during one of my trips, a natural element, unlike the others. The last one is a blanket, a photo taken in Abruzzo again, at Santo Stefano di Sessanio. It is much more intimate. They are three very different images with different depths: one is dominated by the light, which is philosophical, baroque; one has the rarefied atmosphere of rocks in the mountains and the last is warmer with a background colour of dark pink contrasting with anthracite, the pattern of a traditional Abruzzo blanket.

So, from nature to local tradition and to the exotic, as the floor of a museum in Morocco might be.

Yes, of course. Both the blanket and the floor are highly decorative elements, with a very precise pattern, but the image of the landscape has the large rocks in the foreground which also become a very strong element that makes the image distinctive.

Tell me about defining colours.

Colour was an important feature in the Retina project, with the contrasting yellow and black of the Moroccan floor and the pink and anthracite of the Abruzzo blanket, while in the Campo Imperatore landscape we opted for a very dark blue and a pearly white.

To what was the choice of the floor of the museum in Morocco owed? to the pattern, the colour or other reasons?

It was one of the first chosen, in an effort to establish whether the images that were to be submitted to the halftone process were able to render such a complex pattern and the sensation of such a unique material. Let’s say it was also something of a challenge to see if we could manage to transfer a material sensation from one sphere to another.

The choice was also down to the result you desired and subsequently obtained.

Yes transforming a digital image was a lengthy task. I did it myself partly to comply with the technical characteristics of weaving. Some performed better than others and Simone Ciglia helped me a great deal with the choice and definition of subjects to use.

A work on Abruzzo squared, or rather cubed, seeing that there was the commission from Fondazione Menegaz, the work coordinated with Arazzeria Pennese and the subject which, in two out of three cases, comes from Abruzzo itself.

Yes, and seeing as we are talking about dual or triple references, the choice of the blanket, which enabled me to use the pattern of weaving, which then became, in its turn, the subject of another textile work (through Arazzeria), is very interesting.

Contemporary art presents complexities which need to be explained. Today many artists think along these lines. Do you prefer to do it in the first person? And, if so, can you trace the trajectory from your initial idea for Retina to how you would like people to see the finished work?

I don’t have goals, there are no predetermined destinations. It is always an experiment in which the results cannot be predicted and which is, therefore, open-ended. This is the way of working I find suits me best, the one that stimulates me most and perhaps the results are not predictable but this process is the only one that enables me to learn, and I think it is a way of creating an opportunity to exchange and spread knowledge. Me personally and everybody else involved.

Today we live immersed in technology and in a few short years, this has radically altered our daily lives. How has it changed the life of an artist like yourself? Do you think you could envisage one of your works produced say by transposing the work on a computer or on a smartphone?

I don’t work with smartphones but I have certainly been doing exactly this for a long time with computers or with people who know how to use a computer better than I do. I am, necessarily, a part of this digital revolution which has swept us all up. I also have a very clear memory of the need to work in an analogical world and so I am able to apply different sensibilities to computer processes. Artistic projects in the digital age engage with a great deal of new potential and a part of my work- which has been developing below the surface for some time like a kind of karstic river which occasionally gushes forth, in some cases in large works like the church of the new hospital in Bergamo, where I used a digital elaboration of my photographic images for the first time – has reemerged here, but it is a process I continue to work on. Perhaps it is less evident, less visible than other ways of manipulating the image I have tried.

And the idea of producing a work on the computer, or on a smartphone? Could putting one of your works directly on a smartphone be something that might interest you?

It happens anyway. People who want to see one of my works go on the Internet and are guaranteed to find scores of images which are there already. So that happens whether I want it to or not. This is a dimension that involves everyone and it is the reason why I gave up on the idea of creating my own website halfway through, even though I have a domain in my name which will contain my productions in the future. I don’t know. It is an ongoing adventure and my way of working is perhaps a little old-fashioned compared to the possibilities developed by the next generations. I consider myself to be a very limited person but I am also happy to try to learn the characteristics and limits of digital work.

What difficulties are encountered today by an artist who, on the one hand, finds an art scene that is almost complete and, on the other, a world where the image, despite becoming extraordinarily powerful (more than we could ever have imagined), is often reduced to a mere reproduction which is infinitely multiplied thanks precisely to new technology?

In any case, contemporary artists work on the idea that the work of art has to physically exist. It might be free of the limitations of a physical body in relation to a visual or digital work but actually, it is another form of materiality. For us, artists engaging with so many types of different materials is very important and therefore an enrichment.